Heroes, Horses, and Real Estate at the End of the Heartland Dream

A Close Look at What Makes Yellowstone a Red-State Fable That This Blue-State Intellectual Can’t Stop Watching, Part One

As a psychoanalyst, there is no capacity more vital to exercise than empathy. It means viewing the world through my patients' eyes. I may be attracted to or repelled by what I see, but the point is to see. From there, I can think with my patients about the meanings they make of themselves and others and how those meanings inform and perhaps limit their life choices. But I am not a disinterested observer in this process. My own loves, hates, fears, and assumptions distort and illuminate my understanding of the inner worlds of those I'm trying to help.

Something similar is at play when I attempt to make sense of the narrative worlds crafted by popular culture. To appreciate and understand a drama on a small or large screen, I must be willing to enter another's dream. In the case of a movie or television show, it is simultaneously the dream of its creators and the rest of the audience. To really understand this new world, I must allow myself to drift into the fantasy and suspend disbelief. It helps to drop my skepticism, critical thinking, and other cognitive filters and defenses and "just enjoy the show." Of course, as with patients, that is nearly impossible.

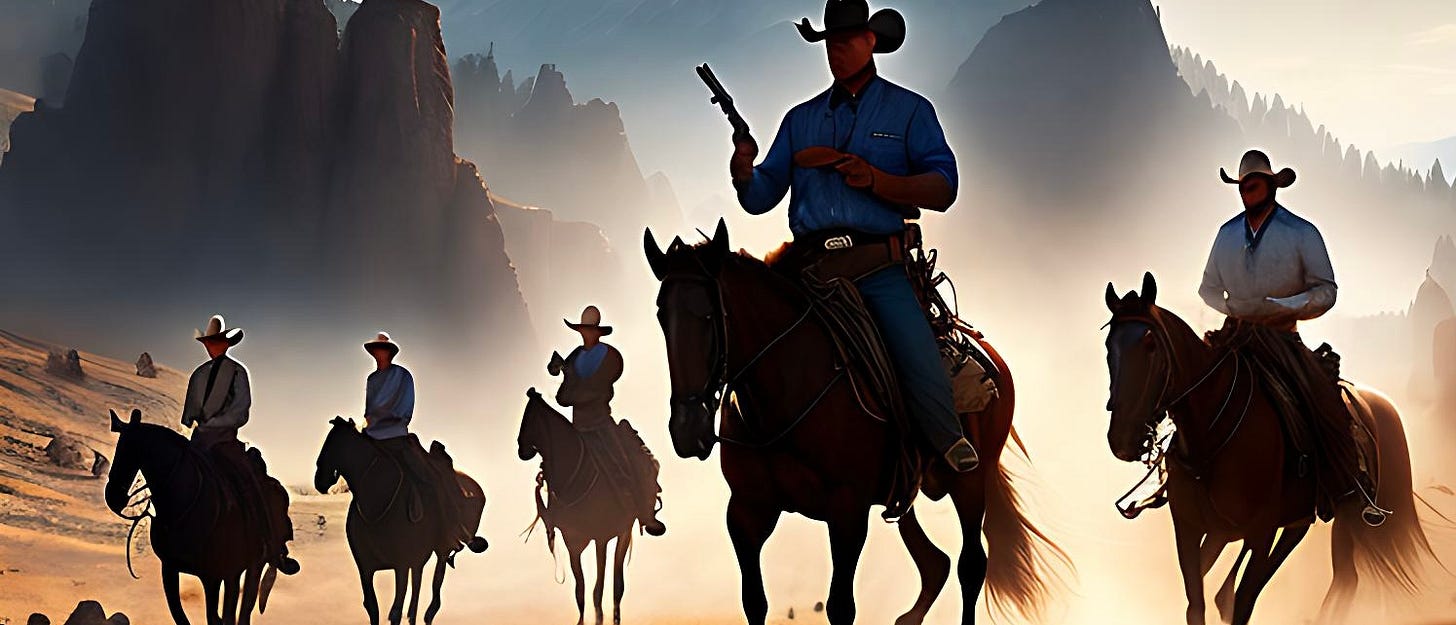

That brings me to Yellowstone, a show that makes me cringe and keeps me profoundly engaged. At times, this dreamscape of cowboy conservatism is one from which I want to wake up but one that also captivates me. A contemporary Western soap opera, Yellowstone, is the most-watched TV show in the country. To understand it and, more importantly, to grasp what has made it so enthralling to so many Americans, especially in red states, it has not been sufficient to sneer at its right-wing assumptions from the outside. I had to enter the world in which those assumptions make sense.

Pardon the tangential association (I'm an analyst, after all), but something about this process brings to mind Attorney General Edwin Meese's Reagan-era antipornography commission. While it produced a 1,960-page report, they were somehow unable to define pornography itself, a frustratingly heterogenous genre. Nevertheless, he and the other priggish arbiters of moral rectitude on the commission, such as fundamentalist Christian parenting oracle and spanking enthusiast James Dobson, assigned themselves the distasteful but strangely riveting task of watching many hours of porn. Of course, that was only to confirm how corrupting it was. And so, to prepare for this article, I made myself watch all five seasons of Yellowstone. That means you, my dear sensitive readers, don't have to suffer the triggering effects of being immersed in every episode of this violent (and entertaining) right-wing fantasy.

Some pundits have dismissed Yellowstone as a multi-season truck commercial. But it would be fairer to describe it as a red-state melodrama – especially when we consider its over-the-top violence, the explosive emotionality of some of its protagonists, its ranch setting, the Republican affiliation of its central patriarch, its celebration of cowboy hypermasculinity, the contempt its characters show for West Coast “elites,” and its deployment of various conservative culture-war tropes. Notably, it has the most uniformly white audience of nearly any TV show. And it is disproportionately popular in the South and Southwest. Yellowstone, like all forms of US popular culture, reflects and shapes how Americans see social reality. My interest here is in the political worldview that might be taken in along with the Trojan horse of "entertainment."

Taylor Sheridan, the program’s writer and creator, bristles at the description of his series as a conservative morality tale and calls attention to the show’s moral ambiguity and its foregrounding of the plight and disenfranchisement of Native people, the reverence that the Dutton cattle baron family hold for the land, and the moral price paid by the greed of its corporate and wealthy villains. There is also an intrepid lesbian investigative reporter. However, the script does note that she hails from the infamous blue-state Gomorrah of Seattle. And she is murdered for her determination to bring down the Duttons.

Rounding out the multi-ethnic palette are several black folks. For example, the Dutton bunkhouse is home to a couple of black cowboys whose race is notably irrelevant, as is the race of all the other African American characters. To ensure the audience does not fail to notice that work-based identity and tribal loyalty supersedes race, Sheridan names one of the ranch hands of color "Cowboy." In other words, this is a “color-blind” world that prizes fealty to the boss’s interests above all other considerations. And beyond the ranch, there are also black corporate attorneys and various law enforcement officers.

We are clearly in the post-racial world that the libertarian right has long insisted America has become. In interviews, Sheridan has decried the concept of "white privilege," at least his strawman version of it. In his reading, the term refers to the putative leftist notion that white people don't suffer from various social ills, such as home foreclosures, poverty, lack of health insurance, and unemployment. He ignores the real privilege enjoyed by white people, which is mostly what doesn’t happen to them because of their race. That includes having less access to medical care, getting profiled and murdered by police, living in food deserts, having their homes under-appraised, getting longer prison sentences, and being more subject to the death penalty. Yellowstone is a fictional tale, not a documentary or a memoir. And it can often be folly to read authors' perspectives into the characters they create. But, in this case, it seems unlikely that the creator's beliefs have not found their way into the imaginary world he has fashioned. Whether he is a witting or unwitting soldier in the right-wing holy war on "wokeness," Sheridan invites his red state audience to stay asleep.

I am reminded of Gunsmoke, and the other 1950's cowboy series, many of which were written, produced, funded by first generation Jewish men. "In the late 1940s, CBS chairman William S. Paley, a fan of the Philip Marlowe radio series, asked his programming chief, Hubell Robinson, to develop a hardcore Western series, about a "Philip Marlowe of the Old West". Robinson delegated this to his West Coast CBS vice president, Harry Ackerman, who had developed the Philip Marlowe series.[4]

Ackerman and his scriptwriters, Mort Fine and David Friedkin, created an audition script called "Mark Dillon Goes to Gouge Eye" based on one of their Michael Shayne radio scripts, "The Case of the Crooked Wheel", from mid-1948. " Wikipedia on Gunsmoke.