Heroes, Horses, and Real Estate at the End of the Heartland Dream

A Close Look at What Makes Yellowstone a Red-State Fable That This Blue-State Intellectual Can’t Stop Watching, Part Four

Justifiable Homicide

There is a patina of justification for nearly every act of violence perpetrated against outsiders by the Duttons – at least enough to find the family less repellant than their enemies. At bottom, only those who can beat, stab, or shoot others with skill and without regret can endure. In this Hobbesian world, one must meet brutality with even greater brutality to survive, let alone thrive. After John Dutton counterpunches, disarms, and overcomes a rival's bodyguard, the bested opponent expresses grudging admiration, saying, "Good move." Without missing a beat, Dutton says, “I don’t have any moves; I’m just meaner.”

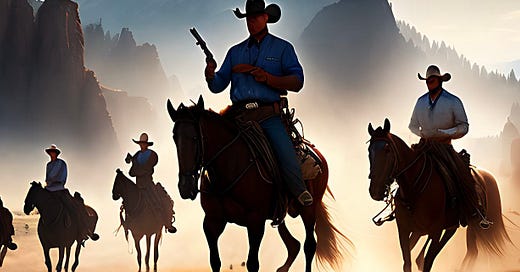

Dutton is part of a long tradition in the mythic lore of the West that the Fargo TV series creator, Noah Hawley, calls the "reluctant hero." He (and it's usually a he) is essentially a vigilante, a dispenser of frontier justice. In the fictional "good guy" universe, this character type includes figures as diverse as Batman and Rambo. And it also describes the way real-life "bad guys" see themselves, self-anointed warriors against evil, such as Timothy McVeigh, the Unabomber, the 9-11 hijackers, and the January 6th army of coup plotters and militias.

When discussing John Dutton's possible run for governor, the outgoing holder of the office, who says she will support him, delicately brings up the possibility that his many crimes, including murder, might be surfaced by opposition researchers. He responds by only half-jokingly saying that his campaign slogan will be "Damn right, I did it!" As much as Sheridan might revile Trump, his reluctant hero character follows the Trumpian tactic of bragging about what most public figures might apologize for, explain, or seek to hide.

Because authorities and the systems over which they preside are weak, fearful, ineffectual, and morally squishy, the reluctant hero must come out of retirement, leave the comforts of his private life, and interrupt his solitary endeavors to step up to evil on his own. He must use any violent means available to ruthlessly defend what can't defend itself – land, children, wives, and livestock. And in autocratic settings beyond the Yellowstone world, that would include religious purity, family values, sexual chastity, racial integrity, or the fatherland. Vigilante saviors "don't need no stinkin' badges," as the Mexican bandit famously proclaimed in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. They don't need warrants, court orders, probable cause, guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, or any of the other legal niceties of due process. They also don’t need others, except as temporary and subordinate allies. Ultimately, only the rugged individualist hero can achieve salvation. He rarely calls for backup. All he needs is moral certainty and the weapons necessary to act on it.

It's Only Natural

Nature is repeatedly invoked to provide rationales for human predatory violence. In a scene following preteen grandson Tate’s first deer kill, the young boy begins to shed tears of empathy at the recognition of the life he has just taken. Grandfather John patiently explains that everything kills something else. Murder is the unavoidable cycle of life. "No one dies of old age," he says. Whether it's a bacterium or a bear, something will kill us. John even attributes predation to trees, which steal the light from other plants. In this bad-faith analogy, part of the story of life is made into the whole story, a reductionism congruent with the conservative worldview.

Left out of this right-wing morality tale are other equally central features of plant and animal life – generativity, nurturance, and cooperation. We now know that is also true of trees, which exist in networks of mutually beneficial relationships with other organisms. The putative harsh-but-unvarnished realism conservatives are so fond of is no less fantastical than the airy-fairy pacifist liberal strawman right-wingers are constantly knocking down. But in the show, the former is presented as the bitter but timeless truth all must accept.

In several episodes, characters frequently find folksy ways of expressing another fundamental postulate that organizes the right-wing mental universe: those who are strong or weak, take power or surrender it, endure or perish are just born that way. What makes this a conservative frame is that in essentializing various social hierarchies and inequalities, they are rendered inevitable and justified. As one cowboy tells the mother of a boy who seems to be recovering well from a traumatic abduction, "You’re either born a willow, or you’re born an oak. That’s all there is to it. He’s an oak.” While drawing on a metaphor from the natural world to convey toughness, he not only promotes the program’s essentialist perspective but privileges rigidity over flexibility, a frequently displayed trait on the part of the story’s hypermasculine protagonists.

The top ranch hand, Rip Wheeler, repeats that lesson when an underling is reprimanded for defying the ranch hierarchy. Rip reminds him that "There're sharks and minnows in this world. If you don't know which you are, you're not a shark." Yes, Yellowstone celebrates nature but primarily the version that is red in tooth and claw. The adopted middle son, Jamie, the Harvard-educated legal consigliere to his adoptive father, illustrates what happens when you don't fight back and just try to use words to manage conflict. (John had sent him to law school to wield language as a weapon but later comes to despise him for relying on such an unmanly arsenal.) Over time, Jamie is reduced to a sniveling, invertebrate weakling whose pleadings for acceptance are only met with further humiliation.

He is an object of disgust for those around him, which at one point devolves into a suicidal self-contempt. Even when Jamie murders to protect the family, it does not have the salvific power that homicide does for others in the clan. It is instead viewed as just one more bungling failure to live up to expectations and is read by other family members as simply self-serving. However, once he meets his ex-con biological father, who murdered Jamie's mother, Jamie thinks the newly discovered kinship reveals his true self. He shifts from the self-negating obsequious son of John to a ruthless usurper of his adoptive father's power and estate. Jamie continues to oscillate between resentful servility and back-stabbing vengeance.