Heroes, Horses, and Real Estate at the End of the Heartland Dream

A Close Look at What Makes Yellowstone a Red-State Fable That This Blue-State Intellectual Can’t Stop Watching, Part Three

Property Rights and Wrongs

Some have described Yellowstone as a soap opera about property rights. The show oscillates between two perspectives. On the one hand, it affirms the 19th Century anarchist Proudhon’s proclamation that “property is theft,” especially as it pertains to the genocidal seizure of native lands. On the other hand, the Dutton empire and land holdings are depicted as earned, hard-won, and worth the body count required to retain. The show ultimately agrees with Proudhon but makes peace with the idea that theft is inevitable. John points out, “You build something worth having, someone’s gonna try to take it,” as the settlers before him had done to the ranch's early Native occupants. The show doesn't hide behind coy euphemisms; those who have resources stole them from others. And that is the inescapable way of the world; the elder Dutton often points out. So, get over it.

But property is also a fetish object. It can function as a trophy representing the spoils of conquest and, thereby, the superiority of one's clan and the inferiority of those from whom it was taken. However, if land embodies power, losing territory means one’s power goes with it. If obtaining, owning, and controlling property is how a clan makes its mark in the world, its loss is the family's erasure from history. Of course, as a ranch, loss of land is also a loss of income. For all these reasons, John Dutton is obsessed with protecting and preserving control over the family estate, sometimes killing for it.

“This is America. We don’t share land here.”

That was John Dutton’s response that followed two warning shots from his rifle issued to an impertinent Chinese tourist whose group had wandered onto ranch property. The foreign interloper had the nerve to assert, "It's wrong for one man to own all of this." We can only speculate why Sheridan chose to put those words in the mouth of a Chinese intruder. While he may dislike Trump, China is the preferred MAGA enemy du jour. In the public mind, especially in his red states audience, Chinese people already carry the symbolic freight Sheridan needs for the outsider characters in this scene. They are non-white and have served as useful scapegoats for the disastrous outcome of the former president’s early failure to take the Covid pandemic seriously and his later efforts to devalue public health measures and deny science. Perhaps more importantly, its governing dictatorship embodies the coercive collectivism that right-wing libertarians are fond of presenting as the only alternative to deregulated predatory capitalism and the privatization of everything. That scene also brings into sharp relief a central border dispute in the conservative imagination and enacted in real-world political battles. I’m referring to the centuries-old conflict between public access to the forest commons and the enclosure of those lands by private interests. It is condensed into the very name of the show.

Yellowstone is about one family’s ranch, not the national park – one clan’s right to possess and control forests, rivers, and mountains versus the right of all Americans to enjoy it as part of our shared and protected legacy. This is not to diminish the hideous irony that this public preserve was enabled through the violent expulsion of its native inhabitants, whose ancestors had been there for eleven thousand years. The ensuing historical fantasy of unoccupied wilderness helped to facilitate the erasure of its prior human residents as well as the ruthless and bloody means of getting rid of them. So, the park stands as a paradoxical symbol. It is simultaneously a monument to the evil of enclosures and the value of the commons.

The story of Yellowstone, the fictional ranch, is more straightforward. It is about the justice of employing limitless brutality to defend the privatization of nature long after it had been ripped out of collective hands. The show is replete with subplots about the incompetent but malevolent and intrusive agents charged with protecting Yellowstone, the park. They are the personification of the GOP's Federal Government boogeyman, a villain to the Right since the antebellum slaveocracy and its battle for the “freedom to dominate.”

The Yellowstone iteration of the classic conservative morality tale is most fully exemplified by the Department of Fish and Wildlife, an agency populated by feckless, meddling authorities whose aim seems to be to protect animal predators and prosecute humans seeking to defend themselves and their livestock. Its officers even put themselves in danger by arrogantly refusing to heed the cowboy wisdom of the Dutton clan.

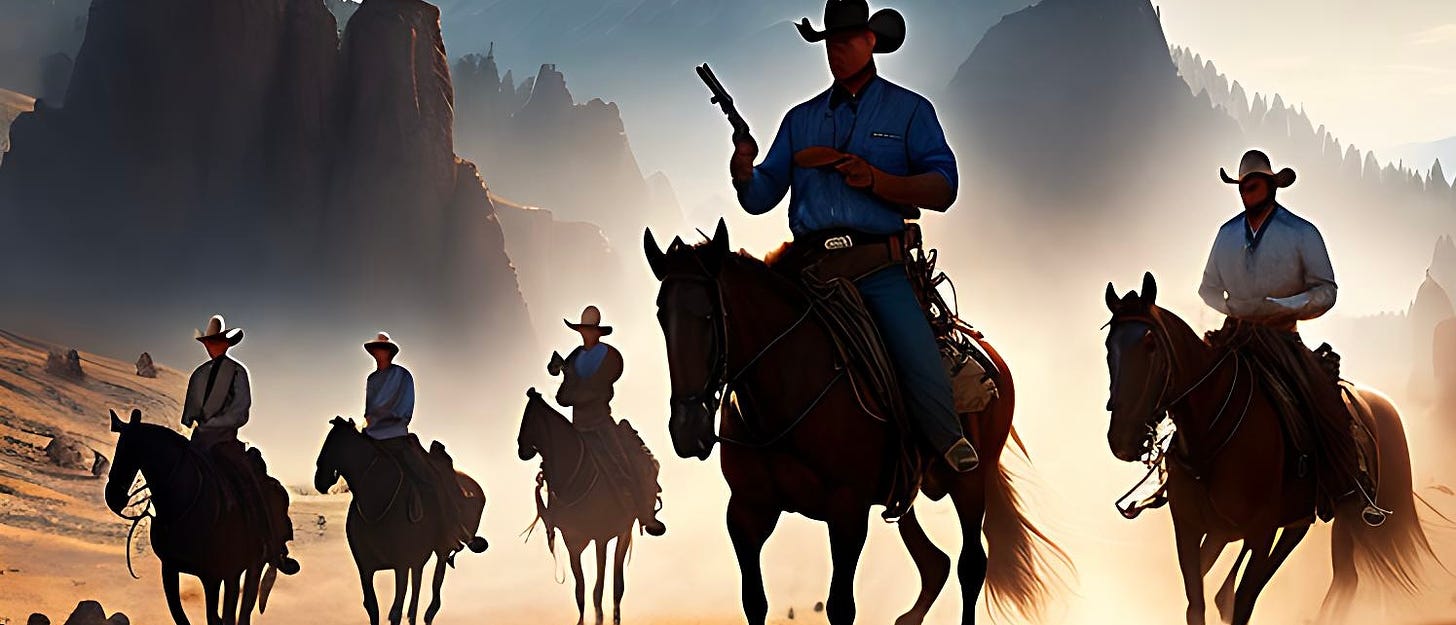

The park’s wolves, violating private boundaries and killing unprotected cattle, earn a death sentence at the hands of ranch workers. Lethal force is the preferred method of managing all predators, human and non-human. The Dutton version of the cowboy way is to shoot first and bury the bodies later. To be clear, I’m not arguing that Sheridan endorses the Dutton approach to property management. But he has crafted a narrative that depicts their brutal methods to be efficient, necessary, rewarding, and ultimately just. And, given the options presented, their actions are quite rational. Again, regardless of Sheridan's personal beliefs, his conservative viewers recognize a gratifying affirmation of their worldview when they see one. It is fandom driven by confirmation bias.

Sacramental Violence

Extreme violence punctuates most of the stories told in Yellowstone. For the audience (at least for myself and those I persuaded to watch with me), the unrelenting depiction of violence itself can be a kind of bludgeon, leading to desensitized indifference. At a certain point, it ceases to be remarkable or even disturbing. However, for the characters, violence is an expected, if traumatizing, part of their existence. And it is not just utilitarian. It is also a path to spiritual purification, a way to prove manhood, a demonstration of loyalty, an insurance policy against future retaliation, a ritual of initiation, and an affirmation of dominance.

The bloody mortification of the body is central to the hard-earned path to manhood. Caring for the body seems to be viewed as a feminizing indulgence that only weakens one’s character. When the ranch hands incur severe injuries, they are denied the services of a physician. Their wounds are tended only by a veterinarian who makes house calls. Jimmy, the formerly self-destructive meth addict, is given a second chance at life and an opportunity to achieve ever-elusive manhood by joining the crew in the bunkhouse. Due to a rodeo injury, he sustains several nearly paralyzing spinal fractures. Following a partial recovery, his doctor insists that Jimmy needs to wear a full-body brace 24 hours a day for a while to avoid ending up in a wheelchair. However, when he travels to a Texas ranch for a kind of masculinizing cowboy internship, a champion horse trainer, portrayed with snarling contempt by Sheridan himself, drives Jimmy there. The trainer demands the brace be removed so it doesn't scuff his pricey alligator-skin seats. With a flare of angry disgust, the horseman tosses the brace in the back of the truck as if it were a pair of soiled frilly panties. Jimmy never wears it after that and does just fine without the support it offered. All that was necessary to stiffen his spine, the story suggests, was manning up at cowboy boot camp.

That is just one of many instances in which doctors are defied when they are consulted for life-threatening conditions. Their recommendations are mocked, and treatment plans are refused. The show recycles the cliched macho medical heroics, now commonplace among TV and movie protagonists, in which the hospitalized cop/soldier/detective wakes up from a near-death injury, yanks out IVs, removes monitors, and tries to leave against medical advice. In Yellowstone, expert help is only a hindrance. What matters is cowboy determination and high pain tolerance.

While men inflict brutal and relentless beatings on one another, amazingly, no lasting injuries are endured, and no brain or organ damage results – just a few cuts and bruises, which fade in a few days and are worn as badges of honor. Violent combat is how cowboys (read "real men") settle disputes. It is also the best path to achieving compassion and fellow feeling. An especially vicious fist and boot fight is set up to resolve an intense sexual rivalry between two ranch hands, a battle that would have put any real human body in the ICU or the grave. In the end, one combatant, Lloyd, graciously offers a hand up off the ground to the other guy, Walker. Days later, Lloyd pawns his prized rodeo buckle to buy Walker a guitar to replace the one he, Lloyd, had smashed in a jealous rage. There is an obvious lesson here for leaders of competing nation-states or litigants in engaged in court battles. Rather than waste time negotiating disputes through boring conversations or tedious legal proceedings, opposing parties could simply beat one another to a bloody pulp. As Sheridan would have us believe, nothing helps people, especially men, see eye to eye more than blackening the other guy’s.

Perhaps in the interest of gender equity, he has the most “ballsy” women also settle their differences with savage fisticuffs. Like the men, their faces end up looking like black and blue hamburger. And also, as with the men, there are never enduring debilitating injuries, and the beatings often resolve lingering conflicts or at least produce a mutual tolerance.